Reproducible Analytical Pipelines

Reproducible Analytical Pipelines (RAP) are an approach to implementing code-based analysis in government, particularly with a view to increasing automation of routine and regular statistical and analytical projects. It was originally developed by data scientists at the Government Digital Service but has since been adopted more widely across the Analysis Function within Government, and is recommended by the Office for Statistics Regulation.

Code first approaches to analysis

It is our ambition to adopt a ‘code first’ approach to analysis. this doesn’t mean that every project must involve extensive amounts of code or that everyone has to be a ‘coder’. Rather, when initiating or updating a project we should think at the outset about whether and how we will use code in that project. And while is isn’t essential that all analysts are ‘coders’, it is important that all analysts understand the benefits and basics of code-based analysis.

The largest benefit of code-based approaches is how they make it easier to collaborate and to audit how work has been undertaken. Moreover it is then easier to repeat and reproduce work - a particular benefit when the same or similar activities are undertaken on a frequent basis. Repeatability can also be maximised within a project. Many projects require the creation of similar tables and outputs. For example a table of headcount by grade for each department. By adopting a ‘code-first’ mindset we can also adopt functional programming approaches in how we write and use code for analysis.

Functional programming

Analysis often involves repeating actions, for example a table of headcount by grade for each department or a table of the engagement index and theme scores from the Civil Service People Survey across different diversity characteristics. Using code-based approaches to create these tables would allow us to more easily QA work by checking how the tables were created. However this might still require multiple lines of code - not just to create the table, but then to format it into a standard output style. Repetition like this introduces opportunity for error.

Instead we can use functional programming to write our own functions that standardise not how a table is created but also how it is formatted. This reduces the amount of manual QA because once the function is built and verified we can be assured it produces the same output time after time. It can also make code more readable for non-coders - a single line of code calling a function called headcount_table is easier to read and understand than several lines of code.

A functional programming approach allows us to move from writing large blocks of code each time we want to produce a table, to a single function call.

From this:

|

|

To this:

|

|

Code Maturity

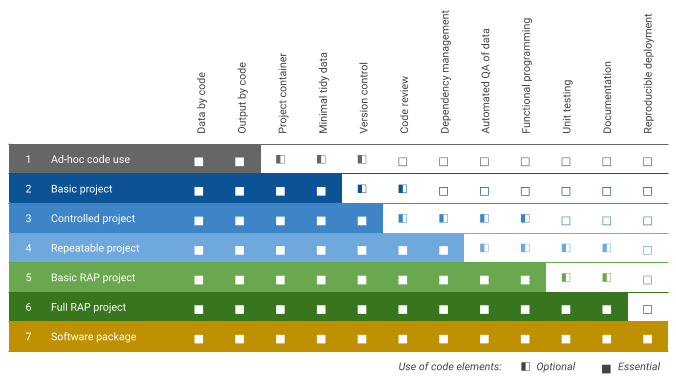

By considering 12 different aspects of code-based analysis we can develop a ‘maturity matrix’ for the use of code in analytical projects. The matrix defines 7 levels of code maturity from ad-hoc use to a full software package.

Code maturity aspects

The 12 aspects to consider when assessing code maturity are:

- Data by code

- Data is imported, cleaned, processed, manipulated and analysed by code-based scripting.

- Output by code

- Output of analysis - tables, charts, reports - are produced by code-based scripting.

- Project container

- Code is stored within a discrete project container - e.g. a distinct folder or an RStudio project.

- Minimal tidy data

- Data is processed into/can easily be coerced into a tidy data structure.

- Version control

- Code is managed with git version control using GitHub, included regular code commits. For advanced projects, git branches and merges using GitHub pull requests is advised.

- Code review

- Code is reviewed by someone who hasn't worked on the project to (i) check it is readable and conforms to standards, and (ii) to identify potential efficiences and improvements.

- Dependency management

- External software dependencies (including software versions) are logged and possibly managed to ensure analysis can be easily repeated.

- Automated QA of data

- External software dependencies (including software versions) are logged and possibly managed to ensure analysis can be easily repeated.

- Functional programming

- Project uses a functional programming approach where functions are developed for common and repeated tasks.

- Unit testing

- Functions within the project code are tested through unit test scripts that can automatically check whether the function operates as expected.

- Documentation

- Functions are clearly documented, explaining their purpose, their arguments and the result(s) they return to the user. The project has at least a README, and preferably other documentation that explains how to (re-)run the analysis.

- Reproducible deployment

- Code is packaged into a deployable software container that makes it easy to share with others.

Code maturity levels

Code ‘maturity’ doesn’t mean that all projects should aspire to be a software package. Each analytical projects will have its own needs - the maturity matrix and levels provide a way of determining the most appropriate level of code use. Our seven levels of code maturity are:

- Ad-hoc code use

- Code is used to only a limited extent for working with data or producing an output. This is most suitable for very small scale tasks or brief ad-hoc data requests. Only the data by code and output by code elements apply.

- Basic project

- Code is used for generating either data and/or outputs. It is held in a container and uses ‘tidy’ data structures. This is suitable for most small scale projects and/or exploratory work. Beyond ad-hoc code, where data and output are managed by code, a basic project will also include project container and minimal tidy data.

- Controlled project

- Building on the basic project, in a controlled project the code is managed using version control to track development of the project and facilitate collaboration. This is suitable for exploratory projects involving multiple people or where a record of the code’s development is needed.

- Repeatable project

- In addition to version control, a repeatable project will involve peer review of code and basic dependency management (e.g. logging software packages used). This is suitable for any project, it is particularly useful if the work will need to be repeated.

- Basic RAP project

- In RAP projects, data and output must both be managed through code. More advanced dependency management techniques should be adopted to ensure projects do not ‘break’ due to changes in dependencies. Where practical, functions should be used to reduce repetition and improve code readability and there should be automated QA of data to easily flag when there are errors in the input data. This should be considered for projects that are repeated on a regular basis.

- Full RAP project

- Building on the basic RAP project, a ‘full RAP’ project will be based on a fully functional programming approach. Unit tests should be developed to verify that functions work as expected. Functions and the project should also be clearly documented. This should be considered for all regular data collections, and statistical reporting.

- Software package

- A software package builds on a full RAP project by ‘wrapping’ the code inside a deployment container that allows others to easily use it. ‘Build’ processes for software packages can also ensure that functions are tested and documented. This should be considered where work will be shared widely with others and/or to standardise common actions.

Implementing RAP principles

While the greatest benefit of applying RAP principles comes from using them ‘end-to-end’ in an analytical project, it is not essential. Depending on the nature of the work it may be more suitable to RAP one or some elements of the work rather than the entire project. This is particularly the case for analysis that might be repeated on an ad-hoc basis. It might make sense to automate the data processing & cleaning but not the reporting. Or there might be a repeatable set of analysis but where the input data might require different “pre-processing” each time to get it into the same format.

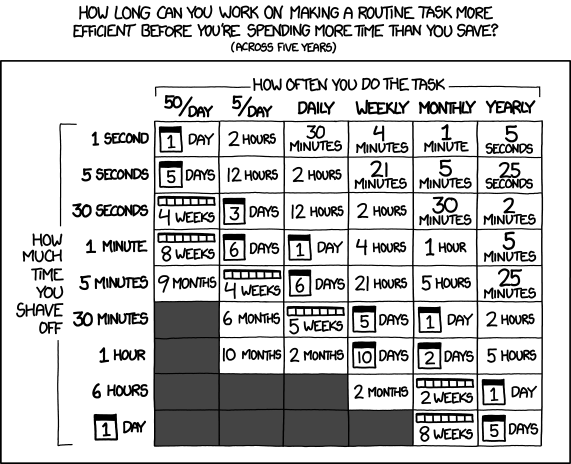

For regular and routine analysis the benefits of standardisation and automation are clear, but there is a trade-off to be made against business as usual delivery. For bespoke/ad-hoc projects there is a careful balance that needs to be evaluated: the time invested in coding the automation versus the time saved from running the automation.

In many analytical projects are suitable for adopting RAP principles within their workflow, either in part or in full. However, a key challenge will be balancing the transition to RAP-based working against delivering business as usual. When starting a new project, or transitioning an existing project, to using RAP the first stage isn’t to jump straight into coding, but to actively think about how the data flows through the project and the key processes involved… i.e. to sketch out the analytical pipeline. This sketch can then be used as the blueprint for building the pipeline.

This sketch/blueprint can also be used to assess what parts of the pipeline are best suited to being integrated into a reproducible process (e.g. that can be automated). For projects in transition to RAP, there is then a choice about whether to build the full pipeline straight away or to adopt an incremental process.

A generic transition plan for adopting RAP principles in an analytical project:

- Sketch the project flow identifying the route data takes from collection through to output.

- Identify key points where automation and standardisation can be applied: (i) importing & cleaning data; (ii) standard processing & analysis; and, (iii) standard outputs.

- Refine the sketch into a pipeline blueprint.

- If transitioning existing work, decide which approach is best and create a plan: (i) running a dummy/parallel process; or, (ii) developing RAP in stages (e.g. focus on one stage at a time).

- Start RAP-ing.

Using Agile principles

The RAP approach has developed out of applying software development principles to analytical programming. Another suite of software development principles is Agile. Agile is a suite of project management methods for software development that focus on iteration and collaboration. The aim of Agile is to focus on iterative and deliverable chunks of work that combine to produce the full product over time, with regular engagement with users and customers. Some of the techniques and approaches used in Agile project management can be beneficial for analytical projects, namely: timeboxes, MoSCoW prioritisation, retrospectives and demos.

- Timeboxes

- Timeboxes, or sprints, are short defined windows of time over which work is organised and delivered. Typically they are one or two week stretches, they start with looking at the ‘backlog’ of tasks and identifying which will be delivered in the timebox.

- MoSCoW prioritisation

- In Agile software development, a ‘backlog’ of product features is maintained which includes all the potential features that a piece of software might do. MoSCoW is a method for prioritising the contents of the backlog, what features are a: Must have; a Should have; a Could have; and, what are a Won’t have.

- Retrospectives

- At the end of each timebox there is a dedicated time for a retrospective about what took place during the timebox: what went well/was enjoyable; what didn’t go to plan/was frustrating; what was tricky/still puzzling.

- Demos

- A key aim of Agile is to develop working components of a software product/service, in part to gain user/customer feedback earlier. Demos are also useful internally within the delivery team, providing opportunities to show-and-tell and spur creativity.